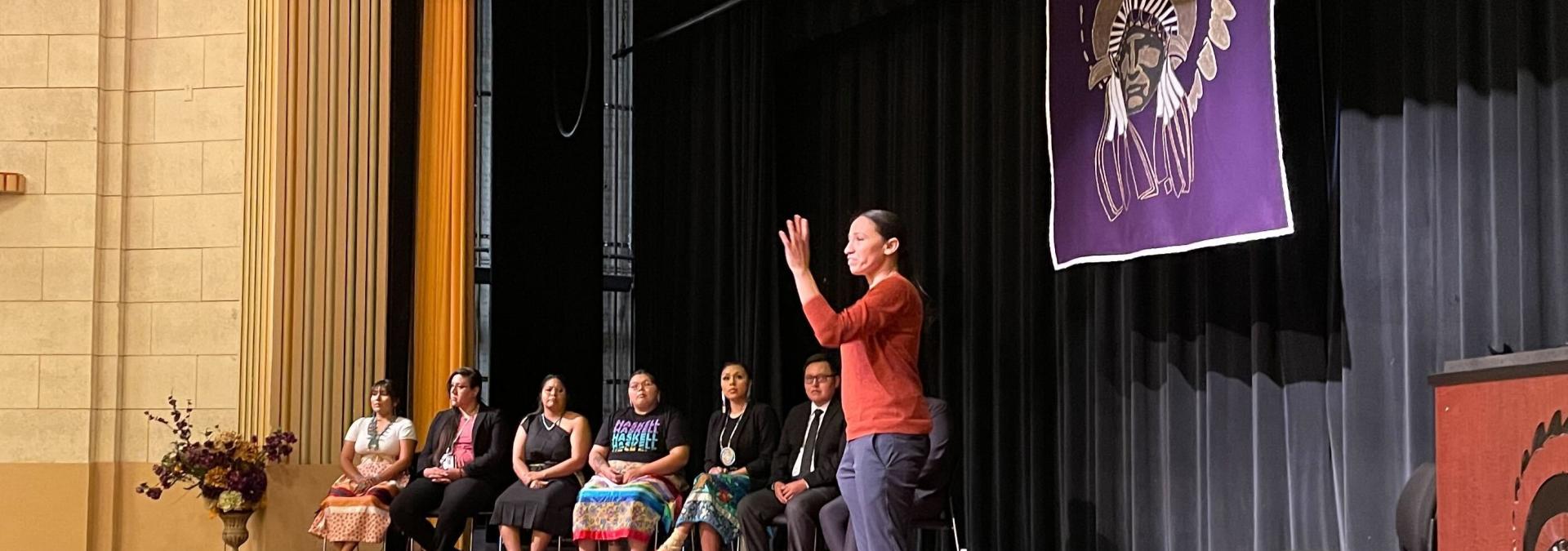

ICYMI: In Guest Column, Davids Highlights a Century of Native American Citizenship

Davids is one of the first two Native women ever elected to the U.S. Congress

Yesterday, on the 100-year anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act, Representative Sharice Davids penned a guest column for ICT News, highlighting the strides our country has made in the last 100 years towards tribal sovereignty. She also advocated for greater federal support for Native communities. Davids, who serves as co-chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus, continues to work diligently to uphold the federal government’s trust and treaty obligations to tribes. Enacted in 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the U.S.

Read Davids’ column in ICT News:

“Today marks 100 years since President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act into law, ensuring all Native Americans are counted as United States citizens. Before this, my ancestors were treated as foreigners in their own land without a voice in the country's most important systems. The act’s passage kicked off a journey for Native American freedom and self-determination that continues to this day.

Generation after generation, Native Americans have worked to ensure our communities receive the full set of rights and responsibilities of U.S. citizenship while protecting the treaty rights that guarantee tribal sovereignty.

Ruth Muskrat, a Native college student who advised President Coolidge on Native American matters, summarized this duality in a 1923 speech: ‘We want to become citizens of the United States and to share in the building of this great nation that we love. But we want also to preserve the best that is in our own civilization.’

The opportunities I have been given, as a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, speak to the progress we have made toward these goals. I am the daughter of a single mother who served in the U.S. Army for 20 years. I worked my way through community college and public university to become the first in my family to earn a college degree, and later a law degree from Cornell University.

Then, in 2019, alongside now-Secretary Deb Haaland, I became one of the first two Native women sworn into the United States Congress. I didn’t run for office to be the first of anything, but it has been an honor to challenge the norms for who our leaders can be and enable others to see a path they hadn't noticed before.

Throughout my career, there have been many times when I was the ‘only’ in the room. That experience is all too common among Native people and so many others. However, we have made significant progress over the past 100 years in ensuring these voices are better represented. I’m working in Congress on various issues to ensure we continue moving forward, not backward.

While the act was a monumental leap in tribal sovereignty, it didn't prevent states from enacting laws that deprived Native communities of their right to vote. While Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, outlawing racial discrimination in voting laws, Native voters still today face many obstacles on election day. To help fix this issue, I have introduced the Native American Voting Rights Act in Congress, ensuring Native voices are fairly heard at the ballot box.

Also, nearly every Native person has been impacted by the federal Indian boarding school era — me included. My grandparents are survivors. Although these histories can be painful, the federal government and our country should acknowledge its impact and listen to Native leaders who seek healing for generations of families affected. That’s why Oklahoma Rep. Tom Cole, Republican and Chickasaw, my fellow co-chair of the Congressional Native American Caucus, and I proposed the creation of a Truth and Healing Commission to investigate and document these policies and address intergenerational trauma.

These examples underscore the critical importance of diverse perspectives in decision-making roles, enabling us to better understand and address the unique challenges faced by various communities. Whether it’s returning our ancestors to their rightful homes, putting names to the children we lost, or shining a light on the continuing crisis of our missing and murdered Indigenous relatives — representation remains the key to solving these problems. It started 100 years ago with the Indian Citizenship Act.

Representation is how we ensure that tribal communities are not left behind in major policy achievements from infrastructure to health care to education.

It is how we bring attention to the disproportionate numbers of Native women who experience maternal mortality and complications in pregnancy, and direct resources towards saving those lives.

It is how we’ve gained recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day to change the way this nation thinks about our history and our modern-day culture.

It is how we remind people that Native communities are resilient, we are diverse, and we are still here.

In 1915, Dr. Carlos Montezuma delivered a speech in Lawrence, Kansas — just outside the district I represent — to the Society of American Indians. He critiqued the federal government’s handling of tribal relationships and encouraged solidarity among Native communities, saying, ‘we must act as one.’

I respect his immense passion for advancing our people and his acknowledgment that the federal government still has much to do to uphold its responsibilities to tribes. Though he passed away just one year before the act was enacted, I also hope he would be proud — just like I am — of the strides we have made.

As the Indian Citizenship Act acknowledged, the Native American story is the American story. If we continue to push forward together — celebrating the enduring Native culture, art, and traditions that have shaped our country — the next century of our shared history will be even greater than the last.”